AsiaTechDaily – Asia's Leading Tech and Startup Media Platform

South Korea Launches 3rd Deep-Tech Startup Cohort from Public Research Institutes

NST and KST select nine new teams from government-funded institutes — but the bigger question is whether structured support can consistently convert public R&D into venture-scale companies.

South Korea is intensifying efforts to translate its strong public research capabilities into commercially viable deep-tech ventures. The National Research Council of Science & Technology (NST) and Korea Science and Technology Holdings (KST) have selected nine preliminary startup teams for the third cohort of the Deep Tech Startup Planning Challenge Program for government-funded research institutes. The program is designed to help researchers transition from laboratory innovation to formal company creation.

Unlike traditional accelerators focused on early-stage founders, this program targets scientists inside public research institutes — a segment often rich in intellectual property but less experienced in commercialization.

Program Structure and Commercialization Support

Commercialising deep-tech research is rarely straightforward. Scientists often possess strong technical expertise but limited experience in market validation, regulatory navigation, or venture financing. This program is structured to close that gap by turning research outputs into investable companies.

It provides end-to-end support across the startup lifecycle — not just advisory sessions, but coordinated execution support. Each selected team receives guidance to transform laboratory results into scalable business models and market-ready ventures.

Core support areas include:

- Business model refinement and commercialization planning

- Founding team structuring and incorporation support

- Linkages to relevant government funding programs

- Intellectual property and regulatory strategy advisory

- Investor readiness and pitch development

Beyond mentorship, every team is assigned a dedicated working group comprising technology licensing offices (TLOs) from their institutes, Korea Science and Technology Holdings, and private expert organizations. This hands-on structure is intended to reduce a common bottleneck in public R&D ecosystems — strong science that lacks coordinated commercialization execution.

NST said the third cohort was selected through evaluation sessions linked to a startup camp in late January. Teams were assessed not only on technological excellence, but also on market potential and execution feasibility, signalling a stronger emphasis on commercial outcomes alongside research merit.

The Technologies: High Risk, High Impact

The nine selected founders come from leading institutes across South Korea, including the Korea Research Institute of Standards and Science, Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology, Korea Institute of Machinery and Materials, Korea Institute of Energy Research, Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute, and Korea Institute of Materials Science.

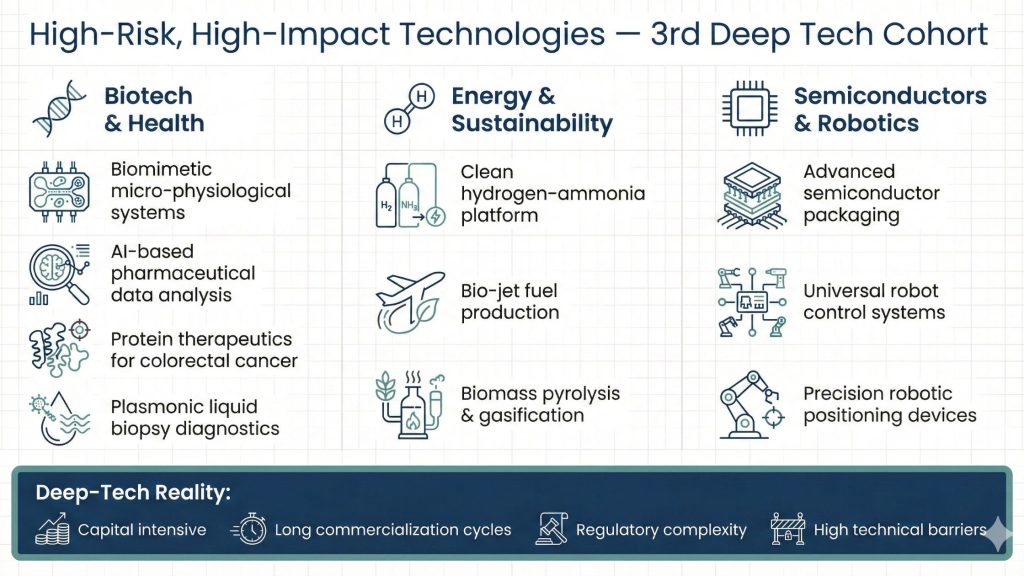

Their technologies span:

- Biomimetic micro-physiological testing platforms

- AI-driven pharmaceutical data analysis

- Protein therapeutics for cancer

- Clean hydrogen-ammonia production systems

- Bio-jet fuel and biomass technologies

- Advanced semiconductor packaging

- Robotics control and precision positioning

- Plasmonic-based liquid biopsy diagnostics

These are capital-intensive, research-heavy domains where commercial success depends not only on technology, but on regulatory navigation, market validation, and long funding cycles.

Why This Matters for Korea’s Deep-Tech Strategy

South Korea has long invested heavily in public research institutes. However, converting research output into scalable startups has historically been uneven.

The program reflects a broader national effort to strengthen technology transfer and commercialization mechanisms. By embedding commercialization planning earlier — before formal incorporation — NST and KST are attempting to increase the survival rate of spin-offs.

Kim Young-sik, Chairman of NST, said:

“We will revitalise the deep-tech startup ecosystem of government-funded research institutes and reinforce practical startup connections that consider both technology and market demand.”

His emphasis on “technology and market” highlights a structural issue: research excellence alone does not guarantee commercial traction.

This third cohort introduces a notable change. Alongside traditional open recruitment, the program now runs an industry-demand-based open innovation (OI) track.

Under this bottom-up approach, large, mid-sized, and small enterprises can signal their technology needs. Researchers whose technologies align with these demands are then matched for startup planning and commercialization.

This adjustment signals recognition that many research-driven startups struggle with early customer validation. By linking industrial demand at the planning stage, NST and KST aim to reduce market-entry friction and shorten commercialization timelines.

If successful, this model could shift the program from a supply-driven commercialization effort to a more demand-linked venture formation strategy.

Early Outcomes and Performance Indicators

The program’s first two cohorts have already delivered measurable outcomes, showing early signs of momentum. According to NST, 13 pre-startup teams secured about 1.6 billion won (roughly US$1.1 million) in government commercialisation funding, and nine companies have been formally incorporated. In addition, five direct or indirect investment deals were executed, and companies emerging from the initiative won the grand prize at Korea’s national “Challenge! K-Startup” competition in back-to-back years.

These results suggest that the support framework — which combines business model development, investor readiness and institutional backing — is helping researchers take initial steps toward market entry. Wins at high-profile competitions also help raise visibility and credibility for deep-tech ventures in a funding ecosystem that often favours software and consumer tech.

However, early outputs are only part of a longer journey. Deep-tech commercialisation differs significantly from conventional software and digital startups in several ways. Deep-tech ventures typically require long research and development cycles, significant upfront capital, and complex validation before any commercial traction.

Where typical software startups might reach revenue or product-market fit in months, deep-tech companies often face extended timelines before pilots, regulatory approvals or early customers emerge. In practical terms, this means follow-on funding — beyond seed and initial grants — is critical for survival. Investors must be convinced not only of the technology’s merit, but of its path to revenue and market adoption, which is often slow and resource-intensive.

As a result, the longer-term test for the challenge program will be whether these ventures can secure sustained private investment, move beyond government support, scale internationally, and deliver economic returns. Success in early funding and competitions is encouraging, but scale and sustainability — particularly in capital-intensive sectors such as semiconductors, energy and biotech — remain significant hurdles.

In other words, the early results show that the program is effective at lifting ideas off the ground and into structured ventures. But the real measure of impact will be whether those ventures can bridge the “valley of death” — the often long gap between prototype and commercial viability — and attract serious follow-on investment to fuel full market entry and growth.

Structural Challenges in Research Commercialization

South Korea’s research institutes produce significant intellectual property across semiconductors, biotechnology, energy, and robotics — sectors central to global competition.

Yet historically, many promising technologies have remained within institutional frameworks or been licensed externally rather than spun out as venture-scale firms.

The Deep Tech Startup Planning Challenge Program represents an institutional attempt to bridge that gap. By integrating TLOs, investment arms, and external advisors early in the process, NST and KST are formalising commercialization pathways that were previously fragmented.

Still, challenges remain:

- Researchers transitioning into founder roles face cultural and managerial adjustments

- Deep-tech ventures require patient capital

- Regulatory approvals in sectors such as biotech and energy can delay market entry

- Global competition for semiconductor and AI startups is intensifying

Execution — not selection — will determine impact.

A More Deliberate Commercialization Engine

South Korea has long been recognised for its research intensity and public R&D investment. The deeper challenge has been converting that scientific strength into globally competitive, venture-scale companies.

The third cohort of NST and KST’s Deep Tech Startup Planning Challenge Program reflects a more deliberate effort to close that gap. By embedding commercialization planning, industry matching, and investment preparation within the research ecosystem itself, the initiative moves beyond one-off spin-offs toward a structured venture pipeline.

The success of this model, however, will not be measured by the number of preliminary teams selected or companies incorporated. It will be judged by whether these deep-tech ventures secure sustained private capital, expand beyond domestic markets, and build defensible positions in globally competitive sectors such as semiconductors, biotechnology, energy, and robotics.

For Asia’s broader startup landscape, the question is not whether public research can generate startups — but whether structured commercialization programs can convert scientific depth into durable market value.

Quick Takeaways

- Nine Deep-Tech Teams Selected: National Research Council of Science & Technology and Korea Science and Technology Holdings have chosen nine preliminary founders from government-funded institutes for the third cohort.

- From Research to Venture: The program targets researchers with advanced technologies and supports them through business model development, incorporation, IP strategy, and investor readiness.

- Sector Focus on Strategic Industries: Selected technologies span semiconductors, biotech, AI, robotics, and energy — areas central to South Korea’s industrial competitiveness.

- New Demand-Driven Approach: An industry-demand-based open innovation track aims to match research technologies with real corporate needs earlier in the process.

- Early Traction, Long Road Ahead: Previous cohorts secured funding and incorporated companies, but long-term success will depend on scaling, follow-on investment, and global market penetration.

- Systematic Commercialization Push: The initiative reflects Korea’s broader effort to turn public R&D strength into venture-scale economic value.